In AD 410, the Roman Empire in the West was falling apart and Saxons, Angles, Scots and Picts were menacing Roman Britain. The British cities appealed to the Emperor Honorius for help, but with barbarian Goths threatening Rome itself, he told them to defend themselves. Thus Britain passed into the Dark Ages, the early medieval period from which Scotland, England and Wales would eventually arise.

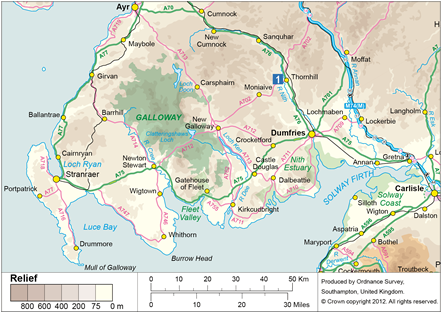

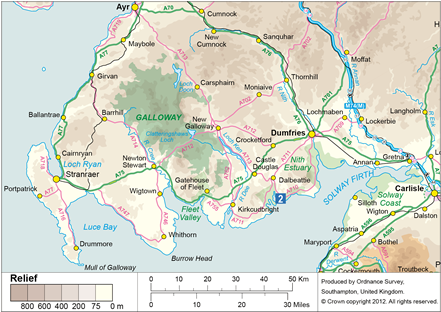

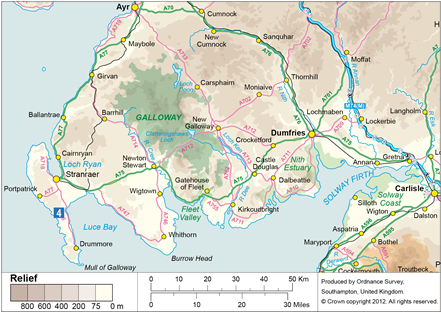

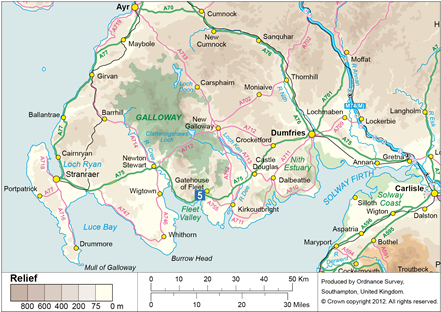

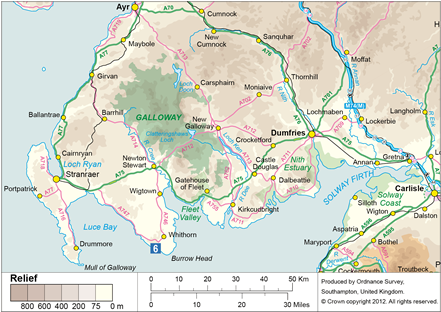

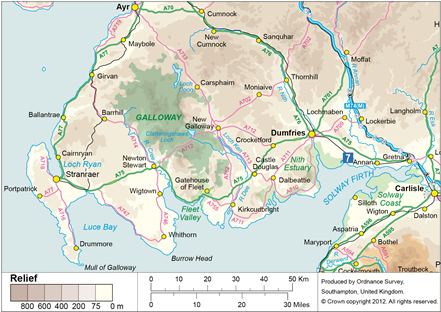

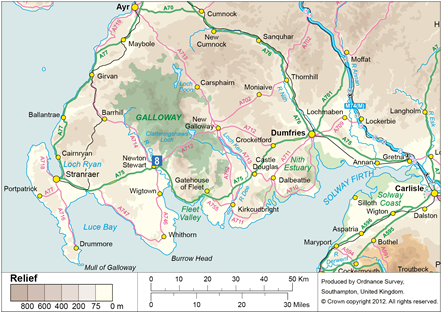

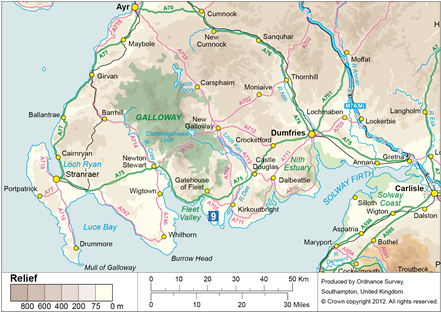

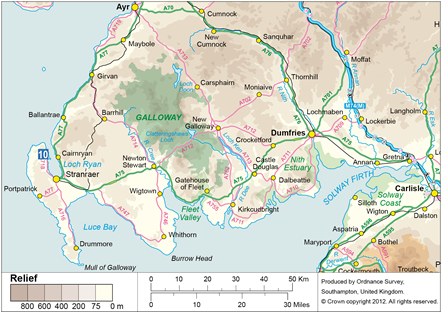

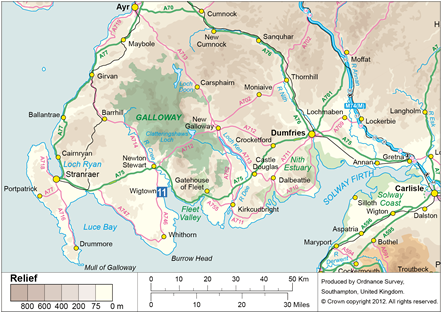

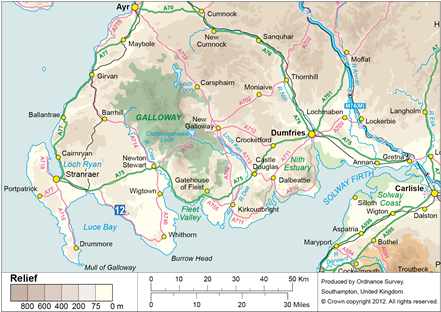

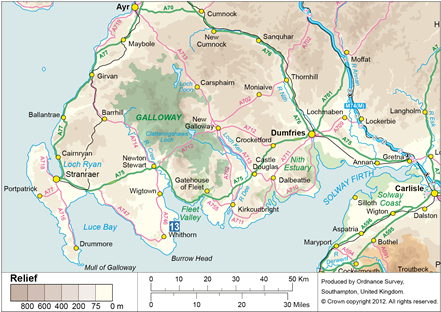

The end of Roman Britain did not come suddenly. The provinces gradually fragmented into small kingdoms. In Dumfries and Galloway, on the fringes of what had once been Roman Britain’s northern frontier, the kingdom of Rheged emerged in the sixth century. Its people were Britons, the descendants of native British tribes like the Novantae, who spoke a form of ancient Welsh. From ancient hillforts like Tynron Doon, small bands of mounted warriors, led by native British princes, waged war upon the neighbouring kingdoms of the Scots, Picts, Anglo-Saxons and fellow Britons. But this was not just a time of conflict. The cultural vitality of this period also survives in the poems once sung by bards like Taliesin and Aneirin at the feasts of mead, meat and wine held in these Dark Age strongholds. The wealth of the British chieftains is demonstrated by the finds of fine pottery from the Eastern Mediterranean and Western France, the decorated glass from the Rhineland and the jet from North-east England recovered from Mote of Mark. Excavations at this site have revealed that a workshop of highly skilled craftsmen was based here, producing jewellery and decorated horse-gear, probably for the court of a local prince.

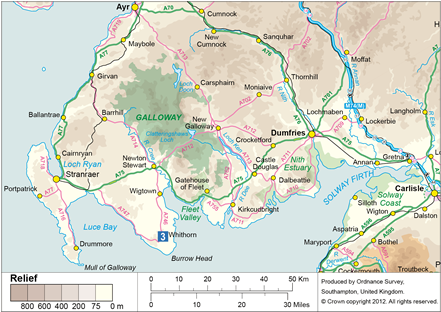

But it was not only chieftains, warriors, craftsmen and poets that benefited from this long-distance trade. At the same time as Roman Britain was collapsing, the first bishop north of Hadrian’s Wall, St Ninian, established his church of Candida Casa at Whithorn. The Whithorn Dig showed that the earliest Christian community used the same fine goods as those close to the court of a local chieftain. Pottery and glass from the Mediterranean and Western France reached this Early Christian Monastery and many of the monks may have come from France itself, bringing new technology and crafts with them. From the beginning, stone memorials such as the Latinus Stone were carved at Whithorn. The early Christian stone inscriptions from Whithorn and Kirkmadrine demonstrate that these communities were literate. They understood Latin and when writing their names used Latin forms. Although the Roman Empire in the West had collapsed, Roman culture was still valued by many people in Northern Britain who still saw themselves as Roman Citizens.

However, it was not only Roman culture that influenced the Britons of Galloway. When not fighting neighbouring kingdoms, local nobility were probably marrying, employing and trading with people from the other cultures of Northern Britain and Ireland, all of which may have left their trace in the way people lived during this period and may have shaped their cultural aspirations. This is the context for the Pictish Symbols at Trusty’s Hill, where the Pictish Inscription either represents the presence of Picts there, perhaps through marriage into a local family, or where a local family aspired to be seen as Picts.

The violent fiery destruction of the hillforts of Mote of Mark and Trusty’s Hill reflect the fall of the British kingdom of Rheged, for during the seventh and eighth centuries Galloway, like much of Southern Scotland, became part of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria. During this period, as Anglian communities settled in pockets of land around the coast, Northumbrian culture flourished, evident in places like Whithorn, where a new Northumbrian church and monastery was built, to which many pilgrims from around the Irish Sea continued to make their way to his shrine. Many Anglian crosses have been found around Whithorn and St Ninian’s Cave and a particularly fine Northumbrian Cross survives at Ruthwell. Other crosses in the region, such as two decorated crosses at Monigaff Parish Church, are more influenced by Irish styles, suggesting that Galloway continued to be a cultural crossroads. A small Irish monastery may even have been established around this time on Ardwall Island not far from Trusty’s Hill.

Viking raids in the ninth and tenth centuries brought about the collapse of kingdom of Northumbria. Excavations show that the Northumbrian Monastery at Whithorn was burnt to the ground during this period of turmoil, to be replaced by a Norse trading settlement. Place name evidence suggests that the Norse, like the Anglians before them, settled in a scatter of sites around the Galloway coast. The old Iron Age stone dun of Castle Haven may have been re-occupied by Norse at this time, giving the name of Borgue (the Norse name for fort) to this district near Kirkcudbright, where a Viking warrior burial was found within the old churchyard. Another Norse settlement may have been near Kirkcolm, where the Kilmorie Cross now stands, depicting Christ symbolically above a Norse mythological figure, thought to be either Sigurd or Thor. This large cross-slab may have been created to celebrate the conversion of pagan Norse settlers as they were gradually absorbed into the mixed community of Britons, Northumbrians and Irish of Galloway. In time an ecclesiastical centre and pilgrimage shine was re-established at Whithorn, where a school of stone sculpture produced decorated stone crosses such as still survive in Whithorn and Wigtown Church. Pilgrims continued to reach Whithorn, landing at places like Chapel Finian and St Ninian’s Cave. It was during this period when the influence of the Kingdom of the Scots to the north began to make its mark, when Gaelic began to be spoken widely in this region. It is perhaps from the name that local people became known by during this period, Galgaels (‘foreign gaels’) that the name of Galloway derives.

Despite all these cultural changes, there survived some elements of continuity, such as revealed by excavations at Cruggleton Castle, which originated as a promontory fort near the beginning of the first millennium AD, but where a timber hall was built perhaps as early as the eighth century and was the earth and timber castle of the twelfth century king of the Galwegians. Fergus of Galloway was the ruler of a principality perceived as distinct from the rest of the British Isles in the culture of its people, derived from their diverse heritage of Britons, Picts, Northumbrians, Vikings, Galgaels and Galwegians, and it was only in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries that Galloway was absorbed into the kingdom of Scotland.