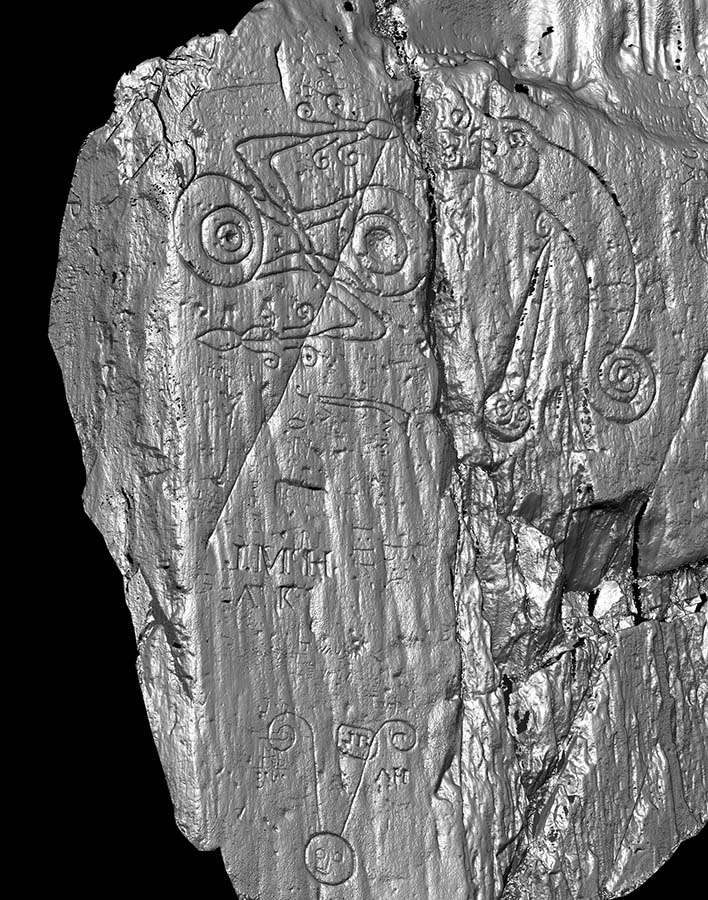

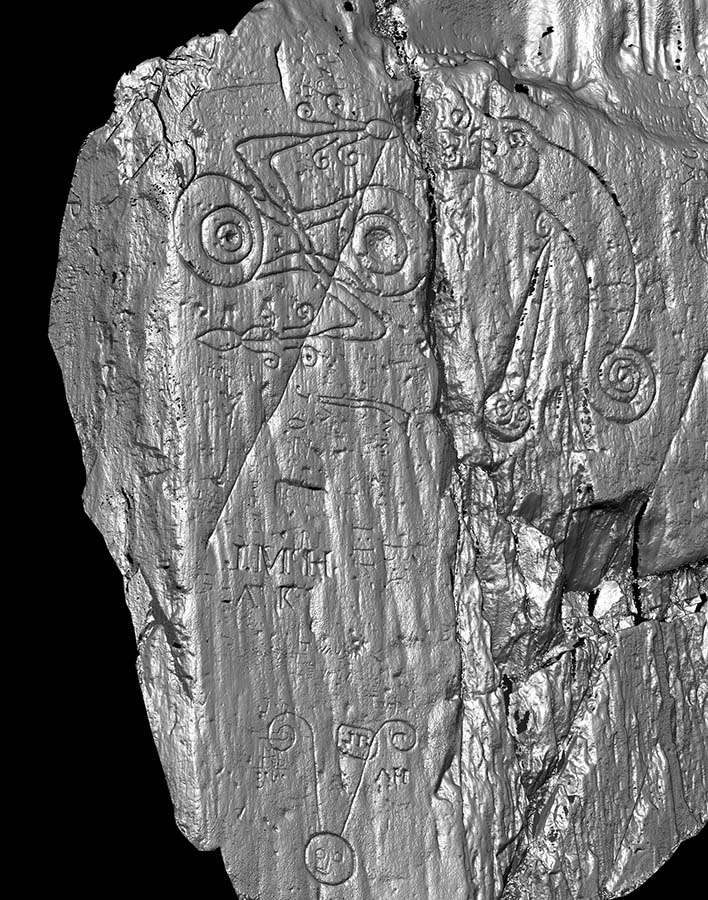

close up of Pictish Symbols at Trusty's Hill

The laser scanning of the carved rock at Trusty’s Hill allowed specialists from Glasgow University to examine the carvings in detail and they concluded that the symbols are genuine and comprise a mixture of Class I and Class II traits – a z-rod and double disc symbol on the left and a dragonesque beast impaled by a sword on the right. The overall impression gained from the study of the left-hand symbol is of a carver aware of Pictish carving on the level of detail but not fully part of the mainstream Pictish tradition. So while the Trusty’s Hill double disc and z-rod symbol has no direct partners in Pictland, which parallel all its stylistic components, the symbol displays a few artistic details or traits that are so basic and common to the Pictish corpus that they could be considered canonical to the form. The right-hand symbol, while again sharing some traits, like the spiral tail, common to other Pictish beasts, is largely unique to Trusty’s Hill. The beast appears to be a form of S-dragon, and while there are a few Pictish comparanda there are also local comparisons amongst the artefacts of the Britons of south-west Scotland. The sharp object depicted to the bottom left of this seems to be functioning as a weapon piercing the belly of the monster – ie the wounding or slaying of a monster, which might arguably give it narrative rather than simply iconic force, which is quite distinct from Pictish symbols.

The specific message intended by these carvings may probably never be recoverable, unless some form of Pictish Rosetta Stone is one day discovered! But the symbols at Trusty’s Hill are not hastily scratched graffiti. Instead they are substantial and carefully laid out carvings in a highly visible location, at one side of the entranceway to the summit of an early medieval power centre. They are positioned opposite a rock-cut basin whose function was very likely ritual (this feature wasn’t a well, there was no spring at the bottom of it and its location outside the summit rampart makes it unlikely it was intended as a daily water source). These two features provided focus to the entranceway in much the same way as the combination of rock-cut basin and a Pictish inscribed rock face at the entranceway to the summit citadel of Dunadd, the royal stronghold of the early Scots kingdom of Dalriada. The combination of the carvings and the rock-cut basin, facing each other, indicates that the approach to the summit at Trusty’s Hill passed through a symbolically charged entranceway where the duelling of inscribed images on the rock face was mirrored in the features of inscribed stone and basin. The ritualised entranceways to the summit citadels at both Trusty’s Hill and Dunadd recalls the complex entranceways apparent in many earlier Iron Age hillforts that appear to emphasis a literal rite of passage between the outside world and the interior of a hillfort.

The symbols are thus part of a multi-element statement about the power of the inhabitants of this hillfort. Whatever the content of that statement it had meaning for a local audience and its likeliest explanation lies in local politics. So far from being evidence of the Galloway Picts, the symbols carved at Trusty’s Hill instead reflect the political aspirations and outward cultural outlook of the Britons of Galloway at some point during the early medieval period.

entranceway to the summit of Trusty's Hill, the carvings lie under the iron cage seen on the left, while the rock-cut basin lies to the right beyond the group of people