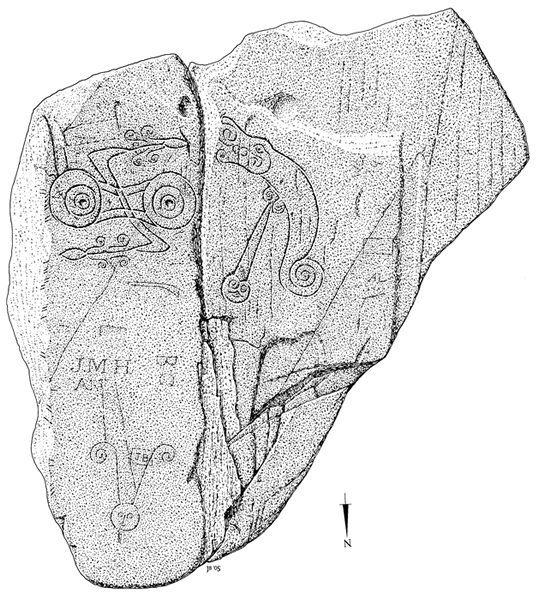

Writing in 1953, CA Raleigh Radford considered the horned head to have been retouched in modern times but thought the form to be old. He pointed out the similar relationship of the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill to two other non-Pictish forts, Dunadd and Edinburgh Castle Rock, which either contain or lie in proximity to Pictish symbols. Based on the reference in the medieval life of St Kentigern to a stone erected to mark the spot where King Leudon fell, Raleigh Radford postulated that these carvings commemorated Pictish leaders who had fallen in attacks on these fortresses. Radford classed the symbols as Class II, i.e. a later phase of Pictish Carvings than what the carvings had previously been classes as, and considered them late 7th or early 8th century by analogy with likely Pictish raids in southern Scotland in the decades following the battle of Nechtansmere (AD 685).

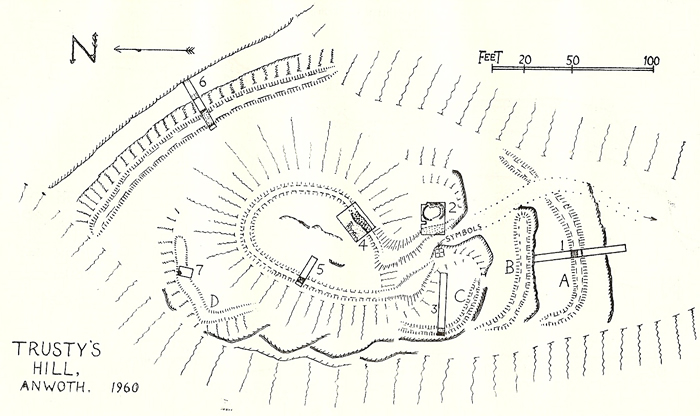

At the suggestion of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, trial excavations were directed by Charles Thomas in 1960, the only known season of excavation undertaken at Trusty’s Hill. This excavation did not recover any precise dating evidence, the only artefacts recorded being the lower half of a rotary quern and some flint flakes and beach pebbles from the interior, which would be consistent with occupation at any time between the second century BC and the early medieval period. A ‘substantial amount’ of bones, from cattle, sheep and pigs, were also found as was charcoal, but none of this was analysed. The rotary quern was found buried face down bedded in an occupation layer near the summit. A waterlogged ‘guard-hut’, composed of a circular rock basin lined with drystone masonry, was exposed near the entrance opposite the symbols. Overall, very little of the interior was exposed, because test pits revealed only bedrock. Vitrification of the internal core of the inner rampart was, however, revealed by Thomas’ excavations. The trenches were subsequently backfilled, other than the ‘guard hut’, which was rebuilt against the north side to a height of six feet, half-pennies being bonded in at the junction of the old and new walling.

Charles Thomas’s Plan of Trusty’s Hill. (Thomas, C 1961 ‘Excavations at Trusty’s Hill, Anwoth, Kirkcudbrightshire, 1960’, in Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society 38, 58-70).

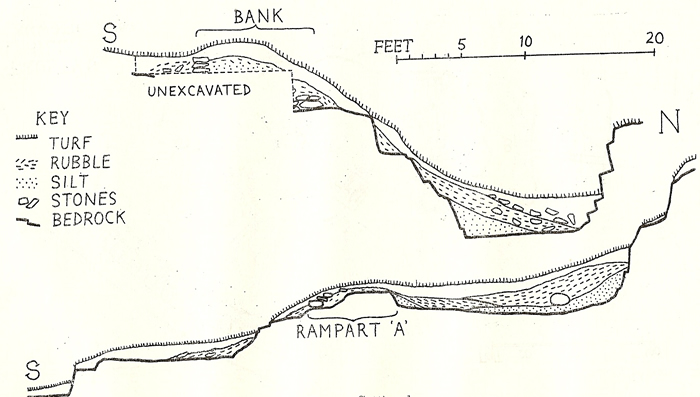

In his report in the 1961 volume of the Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Thomas interpreted two widely separate phases of occupation to the site. The first phase, in Thomas’s scheme, was attributed to the arrival of a new Iron Age group of people in the first century AD. This phase comprised the construction of the rampart around the summit, the ‘guard-hut’ and the rock-cut ditch to the north. In the second phase, the outer ramparts A, B and C were built along with an extension of the entrance. Thomas ascribed this phase to the post-Roman period. The final phase apparently ended with the burning of lean-to buildings and the consequential vitrification of the already partially ruined stone rampart around the summit. Thomas concurred with Raleigh Radford in attributing the carvings as commemorating a fallen Pictish leader responsible for the fort’s fiery demise. However, he considered the Pictish symbols to be Class I, late 6th or early 7th century, based on the apparent improbability of Pictish raiders coming so far south post-Nechtansmere (i.e. after 685 AD).

Charles Thomas’s section of the north-eastern rock-cut ditch and southernmost outer rampart. (Thomas, C 1961 ‘Excavations at Trusty’s Hill, Anwoth, Kirkcudbrightshire, 1960’, in Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society 38, 58-70).

Isabel Henderson, on the other hand, in dismissing early Pictish occupation of Galloway in a paper written in 1960, considered the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill to be a late Class II ‘perversion’, based on stylistic analysis of Pictish symbols. Henderson elaborated upon the principle of the ‘declining symbol’, which recognized the existence of a ‘correct’ form for each symbol and that this form was in the main represented by the earliest examples, and any decline from it by later examples. As the symbols at Trusty’s Hill were considered, according to this principle, to be late and therefore at an otherwise unspecified period ‘when we know there was no Pictish settlement in Galloway’, these particular carvings could be ‘safely dismissed as an outlier’.

FT Wainwright, writing in 1980, also considered the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill, like those at Edinburgh, to be strays out with the main distribution of Pictish Stones in his arguments against Pictland stretching south of the Forth-Clyde. Anthony Jackson went even further in 1984, dismissing the carvings at Trusty’s Hill, as well as at many other sites, as dubious owing to their uncommon symbols. Richard Oram, in his 1993 argument against Pictish settlement in Galloway, agreed that the Pictish authenticity of the carvings was open to question and were possibly relatively modern forgeries. He noted that Thomas’s excavations at Trusty’s Hill, and indeed any other excavations in Galloway, had failed to produce evidence for a Pictish population though, given that symbol-bearing artefacts and painted white quartzite pebbles are the only distinctively Pictish objects in the archaeological record, it is difficult to define what archaeological evidence could demonstrate a Pictish population in the region.

Lloyd Laing observed in 2000 that, since the symbols appear to have been cut at the same time, if the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill were a forgery, as postulated by Oram and Jackson, they must pre-date Stuart’s drawing in the mid-nineteenth century by some duration for him to consider them genuine. Laing commented that this would project any forgery to a period when interest in Pictish symbols was virtually non-existent, but accepted that though the carvings should be seen as ancient, whether they were Pictish or not, was another matter. He accepted the argument that Pictish symbols must be found in pairs to be true and that the double disc and z-rod at Trusty’s Hill were one symbol, not a pair. He also pointed out that the Trusty’s Hill ‘beast’ is similar to a ‘hippocamp’ on a Class II stone at Brodie in Elgin and that hippocamps do not belong to the Pictish repertoire. Ultimately, Laing rejected the sword and symbols at Trusty’s Hill as being genuinely Pictish. Laing considered the style of the z-rod, as it was woven through the double disc instead of crossing it as is the case on Class I stones, to be Class II. He argued that, apart from the horned head and sword which might be Iron Age, the other symbols at Trusty’s Hill were inspired by relief carvings on a Class II monument; that they were executed by someone who had seen Class II Pictish Stones but had not remembered them correctly. As he considered it unlikely that Class II stones pre-date the mid-eighth century, and that the majority are ninth century, Laing therefore rejected the explanation of a Pictish raiding party for the carvings at Trusty’s Hill, preferring instead that the symbols commemorated a marriage between a Pict and a Galloway, perhaps Anglian, noble.

While Craig Cessford, in a paper in the 1984 volume of the Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, admitted that the raiding party theory for the carving of Pictish symbols outwith Pictland had attained the status of a ‘factoid’, and considered a variety of other explanations, he concluded that this theory was still the most likely. However, given the evidence for cross cultural exchange that Cessford sought to highlight, such as the use of Pictish symbols at the royal Scottish stronghold of Dunadd and the adoption of Pictish symbols in the British silver chain from Whitecleuch in South Lanarkshire, it is eminently possible that cross cultural exchange may have happened at Trusty’s Hill as well.

Most recently, in 2008, the discovery of previously unnoticed ogham by an RCAHMS sponsored laser scan survey mirrors the combination of Gaelic ogham and Pictish symbols at sites within north-east Scotland, such as the Brodie Stone in Elgin already mentioned by Lloyd Laing in his 2000 paper as containing similarities to one of the symbols at Trusty’s Hill. Another intriguing parallel may be the Pictish carvings and associated ogham at the fortress of Dunadd in Argyll, the Dark Age capital of the early Scottish kingdom of Dalriada. While the laser scan led to the discovery of ogham, the resolution of the scan, hampered in part by the iron ‘cage’ that protects the stone, meant that the inscription cannot yet be interpreted. However, with a new laser scan planned along with the re-excavation of Charles Thomas’s trenches, the Galloway Picts Project may change this.

Recent RCAHMS Sponsored Survey of Inscribed Symbols at Trusty’s Hill. Derived from information compiled by and copyright of RCAHMS

Ogham is a form of writing using a series of lines with different lengths and combinations, which was developed in Ireland in the first centuries AD and can be found on many of the Early Christian carved stones of Britain, Ireland and the Isle of Man. It is not possible to translate the ogham inscription at Trusty’s Hill at present, but we hope that the laser scan of the stone will allow Katherine Forsyth, an expert from the University of Glasgow, to translate it and perhaps tell us more about why the cultures of three Dark Age groups, Picts, Britons and Scots from Ireland came together at Trusty’s Hill.